The Innovator’s Dilemma reveals an astonishing paradox in business: successful companies tend to fail not because they do anything wrong, but because they do everything right. The theory explains why giants like Blockbuster collapse while disruptors like Netflix rise, showing how the S-curve of innovation and seemingly inferior technologies can reshape entire industries—an idea first introduced by professor Clayton Christensen.

The full story

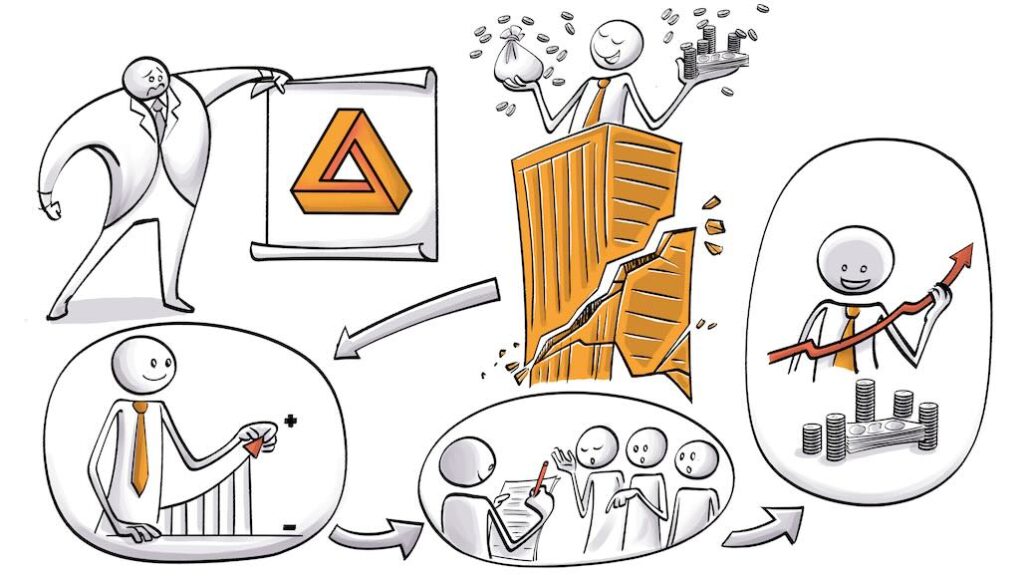

The Innovator’s Dilemma explains a paradox whereby successful companies fail precisely because their leaders improve products, meet customer expectations, and focus on maximizing profits. The fall of Blockbuster is a classic example of such a tale.

blockbuster’s blindspot

At its peak in 2004, Blockbuster operated over 9,000 stores in the U.S., profiting handsomely from in-store rentals and especially late fees. The CEO and other directors thought they were doing everything right. But it turns out they weren’t.

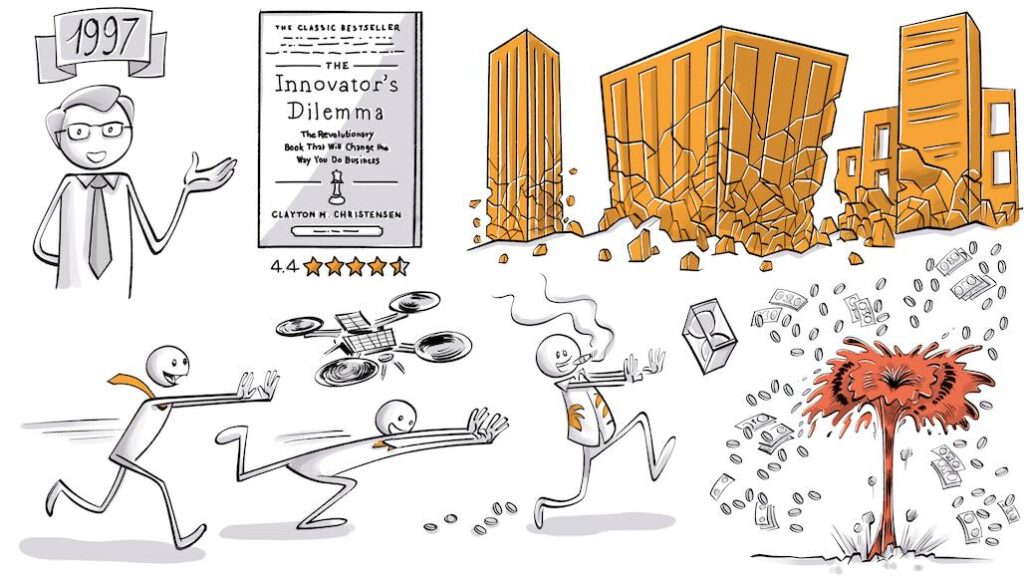

Seven years earlier, in 1997, Reed Hastings, frustrated by Blockbuster’s late fees, had founded Netflix, a subscription video rental service with delivery and no late charges. The service had a relatively small selection of films and orders took a while to arrive, but it appealed to rural customers who lived far from Blockbuster stores.

Studying the competitor, the managers at Blockbuster concluded that Netflix was irrelevant to its customers, who enjoyed browsing shelves for a movie they could watch the same night. So, they dismissed Hastings’s startup, and instead focussed on adding more stores, expanding inventory, and squeezing even more profit from existing customers.

netflix’s breakthrough

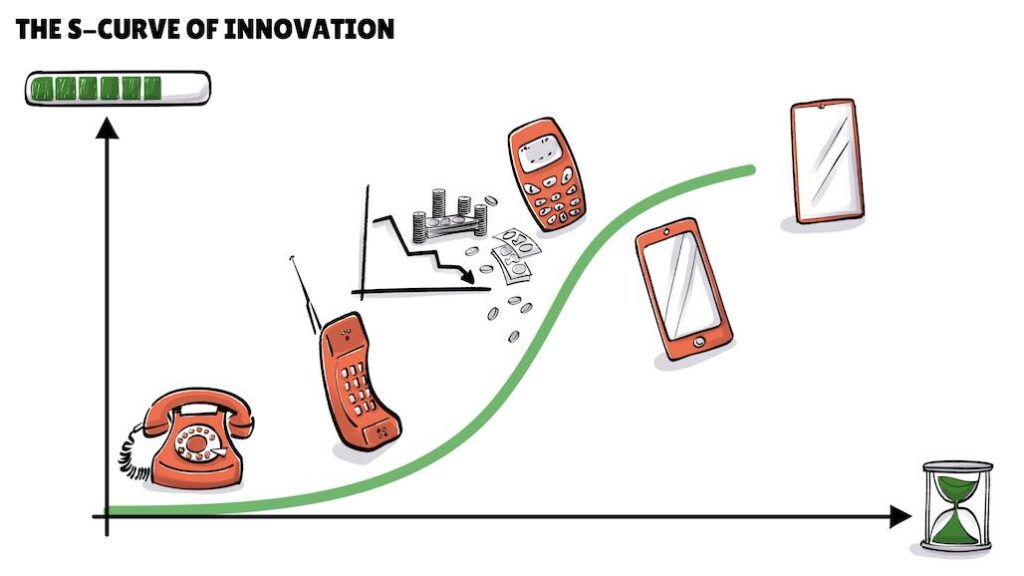

Netflix, meanwhile, quietly gained ground by serving people nobody else did. Then, in 2007, it pivoted to streaming on the internet— a move that was guided by the S-curve of innovation, which illustrates slow progress at first with rapid acceleration as costs fall and technology improves. Three years later, Blockbuster declared bankruptcy.

why leaders fail

According to Harvard professor Clayton Christensen, who introduced the concept of “The Innovator’s Dilemma” in 1997, powerful companies keep failing precisely because their managers, employees, and shareholders chase short-term results—overlooking disruptive innovations.

Ironically, disruptive innovations are often simpler, cheaper, and inferior to their competitors, and have a tendency to create entirely new markets or appeal to neglected customers. But since they look unappealing at first, no one in big established firms can be convinced to invest time or money.

For their leaders, the dilemma is this: stick with proven products or risk everything on untested, disruptive innovations which may cannibalize the existing business model and upset employees and shareholders.

The S-Curve of innovation explains how progress happens over time. In its early stages, it’s slow. Then improvements accelerate, costs drop, and performance increases. Finally, the technology matures and advancements become incremental.

Take fuel-powered cars, which have been at the top of their S-curve for decades with only marginal improvements in fuel efficiency, performance, and safety. Electric vehicles, on the other hand, started out as inferior—offering limited range and high prices—but today, they’re rapidly climbing their own S-curve.

When to jump from one curve to another is the essence of the innovator’s dilemma. Even the savviest CEOs often get it wrong.

disruptive jump

Reed Hastings didn’t miss this opportunity. By the mid-2000s, his DVD rental business was highly profitable. But inspired by Christensen’s insights, Hastings leaped forward into streaming. “Companies rarely die from moving too fast,” he later said, “but they frequently die from moving too slowly.

what do you think?

What do you think about the theory? Are disruptive innovations behind the downfall of all former giants? And applying the theory, what’s the next new thing that will render seemingly invincible enterprises irrelevant in the near future? Tell us your thoughts and experiences in the comments below!

Sources

- Christensen, C. M. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail. Harvard Business School Press.

- Blockbuster (retailer) – Wikipedia.org

- Netflix – Wikipedia.org

Dig deeper!

- Watch Clayton Christensen on YouTube explain Disruptive Innovation.

- Read how the Innovator’s Dilemma impacted the car industry (this example was not included in the video).

- Explore the Christensen Institute’s articles on Disruptive Innovation Theory to better understand the differences and benefits that arise when products or services are disrupted.

- Discover real-word case studies from FourWeekMBA, which provides well-structured analyses of dozens of companies through the lens of disruptive innovation and business strategy frameworks.

Classroom activity

Objective:

Students will understand the concept of the Innovator’s Dilemma and the S-Curve of innovation by analyzing real-world cases and applying the theory to current industries.

Duration:

60 minutes

Materials Needed:

- Sprouts video: The Innovator’s Dilemma

- Whiteboard or chart paper

- Markers

- Case cards (Blockbuster, Netflix, EVs vs. fuel cars, etc.)

- Student notebooks

Steps:

1. Introduction and Video Viewing (10 minutes)

The teacher asks: “Why do even the biggest companies sometimes collapse?” Gather quick responses, then say: “Let’s watch a short video to explore this paradox.”

Play the Sprouts video.

2. Group Mapping: Tracing the Pencil (15 minutes)

Divide students into small groups. Each group uses a map to trace the journey of the pencil’s materials (e.g., wood from the U.S., graphite from South America, rubber from Asia). Mark each location and identify its role in pencil production.

3. Group Presentations and Synthesis (10 minutes)

Groups present their maps and discuss: Who was involved? Were they coordinated by one authority?

The teacher guides students to recognize the decentralized nature of this cooperation.

4. Whole-Class Discussion: The Free Market (15 minutes)

Discuss:

- What connected all these people?

- What role did prices and trade play?

- Could this have happened under a centralized system?

5. Reflection and Sharing (5 minutes)

Students individually write a short reflection: “What does this pencil teach me about the world economy?”

Volunteers share their thoughts to close the session.